The Status of the Wolf - 1. Introduction

|

| © B&C Promberger |

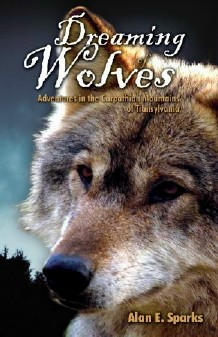

To coincide with the release of Dreaming of Wolves: Adventures in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania, published by Hancock House Publishers, I am pleased to write a series of articles summarizing the current ecological and legal status of wolves in the wild. I will begin with the status of gray and red wolves [1] in the lower 48 states of the United States and continue with wolves in other regions as I have time.

As keystone species, wolves have played a major role in shaping the content and dynamics of ecosystems and in the evolution of valued (by wolves and humans) game animals such as elk, caribou, bison, deer, and moose. In addition, wolves and humans share a long history of interaction – a long history of competition and conflict, and, in the case of one subspecies of wolf, the domestic dog [2], a long history of cooperation and friendship. But as humans have come to dominate the earth’s physical environment, the status of wolves in the wild has come to depend almost entirely on human attitudes about nature, wildlife, and the role of large predators. Thus the evolving status of the wolf during the last few centuries is largely a story about shifting human values.

From Dreaming of Wolves:

“The degree to which an ecosystem is wild and sustainable

is measured by the viability of the animals at the top of the food chain. Predators, particularly the large

and “dangerous” predators, have come to symbolize what little of the world remains wild and free.

Like many lovers of wilderness, I’ve always had an appreciation for these animals, for their beauty,

intelligence, and strength, and I’ve always been especially fascinated by wolves, which happen to share

with my domesticated canine friends a relatively recent ancestry.

For countless millennia, wolves were an integral feature of northern

ecosystems. Populations of the adaptable canine spanned all the great landmasses encircling the Arctic Sea.

In North America, they roamed the frozen tundra and boreal forests of Alaska and northern Canada, the mountains

of the west as far south as the arid uplands of Mexico, the open expanses of the central plains, and the lush

deciduous forests of the east. Across the Bering Strait, wolves inhabited lands of similar features

and climes: the frozen Siberian tundra, the taiga of Russia, the vast steppes of central Asia, the temperate

forests that span the middle latitudes and blanket most of Europe, and ranging south into the deserts of the

Middle East and the jungles of India. Yet, while robust populations of wolves still exist in Russia, Canada,

and Alaska, and scattered remnants linger elsewhere, during the last century and a half the wolf has been forced

to relinquish most of its former domain.

Wolves long shared the diverse landscape of the northern third

of the planet with another intelligent, social, and adaptable predator — one that walks upright on two legs.

Wolves and early human hunter-gatherers not only shared the land, they also shared an ecological niche, competing

for essentially the same prey. Given that the two species faced such similar dynamics of nature — the same

landscape, the same climes, and the same prey — it may be no coincidence that the size and organization of

their social structures and methods of hunting in cooperative groups were also remarkably similar.

But the competing species were bound to conflict, and by medieval

times human attitudes about wolves had descended into dark depths of imagination and fear, as

the wolf came to personify evil in the myths and legends of Europe. Among the early Europeans who migrated to

North America, these beliefs, along with a general desire to subdue all things wild, led to a ruthless campaign

to completely eradicate wolves from the landscape. The last wolves in New England were exterminated by the mid

nineteenth century, around the same time that Bram Stoker penned Dracula, the popular horror novel that helped

to foster a mythological image of the Romanian province of Transylvania as a frightening abode of evil —

and, not coincidently, a land of marauding creatures somewhat resembling wolves.

By the [mid] 1900s, the eradication of wolves was essentially

complete in the lower forty-eight states of the United States, except for [a few stragglers here and

there and] a small population that survived in northern Minnesota. Today, with legal protection, reintroduction

programs, and natural migration, wolves are making a comeback in the United States — in the Northern

Rockies, the Upper Midwest, marginally in the Southwest [and Southeast], and possibly in the Northeast.”

In the next article I will provide a brief account of the wolf’s demise in the lower 48 States of the United States and the status of the wolf as of about 1973 when the Endangered Species Act was passed protecting wild wolves. In succeeding articles I will focus on the current status of wolves as they are now geographical divided into separate populations, each with distinct issues of ecology, law, and co-existence with people: The Gray Wolves of the Eastern US, The Gray Wolves of the Western US, The Mexican Gray Wolf of the Southwestern US, and The Red Wolf of the Southeastern US.

— Alan E. Sparks, author of Dreaming of Wolves: Adventures in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania

FOOTNOTES

- Until recently, the gray wolf (Canis lupus) and the red wolf(Canis rufus) were the two accepted wild species of wolves in North America. Some taxonomic schemes consider the “eastern wolf”, originally inhabiting southern Ontario and Quebec and probably northwestern New York (and now only portions of this area in Canada), as a subspecies of gray wolf (Canis lupus lycaon) and some now classify it as a separate species of its own (Canis lycaon); some researchers believe Canis lycaon should also include the red wolf. As of August 2011, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, as part of it’s ongoing management of wolves in the US as endangered and threatened species or populations, has proposed recognizing Canis lycaon as a separate species. The details of the taxonomy of wolves are complex, controversial, and changing.

- Most taxonomists classify the domestic dog as a subspecies of gray wolf (Canis lupus familiaris) although some consider it a separate species, Canis familiaris. In any case, all dogs are descendents of wild wolves.

© 2011. Alan E. Sparks. All rights reserved.

NEXT – Part 2: Wolves' Demise