The Status of the Wolf - 3. Back from the Brink

|

| © SteffenLeiprecht/Froggypress.de |

Just as the end for wolves in the lower 48 states of the United States seemed imminent, shifting public attitudes led to a dramatic turnabout in their fortune. Starting in the 1930’s a few researchers, such as Aldo Leopold, Olaus Murie, Sigurd Olson, William Feeney, and A. M. Stebler [1], had begun to question presumptions about the entirely negative impact of wolves on game populations. Through field research and analysis they began to recognize the true complexities of healthy ecosystems and the important role that large predators play. Perhaps not coincidently, this new scientific viewpoint coincided with a gradually evolving value system within society at large with regard to nature. People began to view nature as not just an enemy to be feared, subdued, and exploited but as a vital aspect of the world possessing intrinsic aesthetic and spiritual value. Nature became something to be enjoyed and appreciated. A significant number of people began to recreate in the wild places, and some people even began to appreciate and value wolves.

By the late 1950’s this new attitude began to be reflected in public policy. State bounty systems were repealed: in Wisconsin in 1957, in Michigan 1960, and in Minnesota 1965 [2]. Wisconsin granted “full” legal protection to wolves in 1957 and Michigan did so in 1965, even though wolves were essentially already extirpated in the state, with no evidence of breeding packs at the time.

It turned out that the elimination of bounties was all that was required to start a reversal in the prospects for wolves: the last remaining population of wolves deep in the woods of northeastern Minnesota began to recover, expanding from a low of perhaps 300 sometime in the 1960’s to about 750 by 1970. Meanwhile the shift in policies continued. In 1967, under the federal Endangered Species Preservation Act (passed the year before), eastern gray wolves in the Midwestern states and red wolves in the Southeastern states were granted full protection on federal lands. In 1969 Minnesota changed its predator control program to only allow the elimination of wolves that were believed to be preying on livestock. And then in 1973, in legislation that was to become a landmark for the fate of the wolf (and several other endangered species), the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) became law. The ESA extended federal protection to wild wolves in 1974, whether they lived on federal, state, or private land. Specifically included were red wolves and the four subspecies of gray wolves then recognized as possibly still living in the wild in certain designated regions, even if only as lone dispersers or very small, non-sustainable populations: eastern gray wolves (then known as “timber wolves”), northern Rocky Mountain gray wolves, Mexican gray wolves, and “Texas gray wolves.” As “endangered” species listed under the ESA, the wolves could not be legally “taken” (i.e., killed, captured, kept, traded, harmed, or harassed) without a permit, which originally could only be issued for conservation or scientific purposes [3].

In addition to the protections from persecution, the ESA contains provisions directing the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to develop recovery plans for species listed as endangered, including the protection of critical habitat if deemed necessary. Under such a plan the effort to collect the last remaining wild red wolves for captive breeding was intensified beginning in 1973, and a similar effort was begun for the Mexican Gray wolf in 1977. In 1978 the FWS eliminated the gray wolf subspecies designations and extended endangered species protection to all wild wolves found anywhere in the lower 48 states, except in Minnesota where they were downlisted to “threatened” [4]. In the same year the FWS developed a recovery plan for eastern gray wolves which included two specific goals: to ensure the survival of the wolf population in Minnesota, and to establish at least one “viable” population somewhere outside Minnesota and Isle Royale.

Wolves quickly took advantage of their new legal status. The earlier course of their shrinking numbers and territory ran in reverse, as the Minnesota wolf population continued to grow and successfully disperse, reaching the forests of northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan by the late 1970’s. Yet, progress for the wolf was not without opposition and setbacks. For example, an active reintroduction of four wolves in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in 1974 failed when three were shot and the fourth killed by a car.

Wolves outside the Midwest were also on the move. By the late 1970s lone wolves were found dispersing from Canada into northern Montana, and by 1986 a wolf pack was discovered to be raising pups near Glacier National Park. Reintroduction programs in the 1980s and 1990s led to small restored populations of red wolves in North Carolina and Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico, and the active reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in the mid-1990s sped the recovery of gray wolves in the northern Rocky Mountain region. Under the ESA, the actively reintroduced wolves could be (and were) listed as “experimental, non-essential populations,” which means they are subject to more lethal control than are any wolves that migrate on their own.

Today, as wolves are returning to areas in the Western Great Lakes and Northern Rocky Mountain regions, and marginally in small areas of the Southwest and Southeast, conflicts, controversies, and passions are on the rise. Wolf-related stories are often making headlines in these regions, as some people vehemently support the presence of wolves and some people vehemently oppose it. The March, 2010 issue of National Geographic Magazine featured this situation in its cover story, Wolf Wars. Yet many conflicts are triggered by false perceptions. A study conducted in the Central Forest Region of Wisconsin, for example, found that of 52 complaints of livestock depredations by wolves between 1996 and 2006, only 27% were caused by wolves: 25% were caused by coyotes, 11% by dogs, and 29% by causes such as still-births and car collisions.

The return of the wolf has also brought new knowledge about the ecological role played by wolves, as researchers have begun to discover significant consequences that occurred as a result of their absence. In Yellowstone National Park, for example, the return of wolves has led to the recovery of the natural vegetative cover of aspen, willow, and cottonwood that had been reduced or eliminated by elk, especially in some riparian areas. The elk had been able to over-browse both because they could exist in greater numbers without their natural predator, and also because they could be less vigilant and browse in one place without the constant threat. The return of trees has reduced erosion along stream banks and has led to a set of secondary effects – termed a “trophic cascade” by ecologists – including a recovery in the numbers of songbirds and beavers, and even in the numbers of fish and amphibians as more beavers create more wetlands and more insects fall into streams from overhanging branches. Also, the number of coyotes has declined to levels more typical before the elimination of the wolf, allowing more mice and voles, which support larger populations of raptors and foxes. And since animals killed by wolves are on average bigger than those killed by coyotes, wolves may be creating more opportunities for carrion feeders such as eagles, ravens, magpies, bears, and coyotes. A recent study has concluded that the decline in coyotes also may be the cause of more hares in the historical range of the lynx, which should benefit the critically endangered feline predator. Meanwhile, in the Midwest, the population of the wolf’s primary prey, white-tailed deer, has actually risen in many areas along with the rise in the number of wolves. It is not believed that wolves have caused this increase in deer – it is presumably due to weather conditions and an increased availability of browse – but it shows that wolf predation is not always the limiting factor for prey populations.

Like all ecological equations, however, whether such effects are “beneficial” depends on what you value (or on whether you are an elk or coyote, or a deer or fox). Under evolving legal mechanisms (to be described in subsequent articles) the recovering wolf populations in the US are intensively monitored and managed, and since public acceptance of wolves is one of the two primary forces determining the viability of wolf populations (the other being the availability of prey), the long term prospects for the wolf in the US depends highly on public attitudes. And not just the attitudes of the majority: a small minority of determined individuals can effectively threaten the survival of wolf populations in the wild.

Thus the future for the wolf in the US depends on human perceptions about the costs and benefits associated with the presence of this adaptable predator, as well as how the costs and benefits are distributed. Research, effective management, the development and use of effective livestock protection methods, and education will continue to play a key role in the evolution of public attitudes and the fate of the wolf.

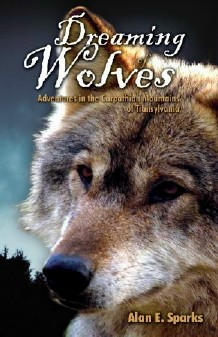

— Alan E. Sparks, author of Dreaming of Wolves: Adventures in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania

NEXT – Part 4: The Wolves of the Western Great Lakes RegionFOOTNOTES

- They followed the lead of P. Errington, a graduate student advised by Leopold who completed one of the first scientific studies of predation, not specifically involving wolves.

- As of today not all states have terminated their wolf bounties. The Colorado wolf bounty, for example, is still on the books.

-

Animals posing an immediate threat of inflicting bodily harm on a person can be legally be killed under

the ESA, but no provisions were provided for lethal control of wolves to prevent livestock depredations.

Later amendments to the ESA allow permits to be issued for the “incidental” (i.e., accidental) taking of endangered species that are likely to occur as a result of some activity. This may sound like a loophole. -

A species may be listed as “threatened” under the ESA when it is determined that the species is “likely to

become endangered within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” In

the case of the wolves in Minnesota, practically this designation meant that wolves preying on livestock

could be killed by federal animal control personnel.

Additionally, within the categories of endangered and threatened, a geographically distinct population may be designated as “experimental.” Experimental populations are further categorized as “essential” (critical to the survival of the species) or “non-essential.” Non-essential experimental populations may receive less stringent protections than other populations of the species. The intent is to allow flexibility in the management of such populations for the purpose of experimenting with policies.

© Alan E. Sparks. All rights reserved.

NEXT – Part 4: The Wolves of the Western Great Lakes Region