The Status of the Wolf - 5. Wolves of the West

|

| © Steffen Leiprecht |

Note: This article provides a summary of the recent history of the legal and ecological status of wolves in the northwestern and western-central United States. This is a complex story - although I've tried to be concise, I've also tried to be thorough. Those wishing to read only a brief synopsis of the most recent status may skip ahead to the Current Status section (updated March, 2012).

The war against the wolf in the Western United States during the late 1800s and early 1900s was especially virulent. As more of the landscape was allotted to livestock and more of the wolf’s natural prey was eliminated (especially buffalo), wolves preyed more on the ungulates most available to them – domestic livestock like sheep and cows – and the campaign against the predator escalated [1]. While the war was fueled by economic interests (not only to protect livestock and reap bounties, but also for pelts), unreasonable fear and hatred motivated some wolfers (people who killed wolves) to not only kill but also torture their targets. Wolves were burned alive, clubbed, hung, or left to starve with their lower jaws cut out or their Achilles tendons severed. Yet, in spite of the veracity and persistence of their pursuers, wolves proved to be resilient, and some individual wolves even became legendary for their ability to elude hunters and trappers.

But the most effective weapon used against wolves, poison – particularly strychnine (in the beginning) and compound 1080 (later) – ultimately left them little chance. The poison was usually seeded in the bodies of dead animals and caused agonizing deaths not only for wolves but also for millions of other animals that happened to come along to feed on the toxic carcasses, such as coyotes, badgers, foxes, ferrets, weasels, raccoons, hawks, eagles, ravens, bears, and dogs. In their strychnine-induced death throes, animals often slobbered the toxin onto the grasses, to which grazing animals such as horses, cows, and antelope could succumb for months and sometimes years later. Sometimes unsuspecting humans were exposed to the poisons, including children.

By the 1940s the war was over in the West. The only wolves that could still be found in the Rocky Mountain region were occasional lone dispersers wandering into northern Montana from Canada. Sheep and cows and the people who raised them no longer had to worry about wolves (and not much about grizzly bears, although coyotes did their best to fill the void). But neither did elk and deer, and the absence of the apex predator began to have ecological effects, especially in areas which had been set aside - primarily for their natural wonders but also with a goal of preserving at least some degree of wildness, with limited or no human hunting. While bears and coyotes can occasionally take a very young or old or sick elk, and cougars take their share, in many areas wolves had been the only significantly effective predator of the large wild ungulates (although they too are more likely to take calves or infirm animals). In the largest and best known such preserve - Yellowstone National Park - after the elimination of wolves it became necessary to cull thousands of elk in order to prevent over-browsing and the consequent degradation of habitat in the park. Elk wandering out of the park were also causing problems for neighboring ranchers, breaking fences and munching on crops.

By the 1970's the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) had a directive under the ESA to restore wolves to the Northern Rockies region - or at least to protect those which might wander into the US from Canada – and environmental and wolf advocates saw the situation in Yellowstone as an opportunity. At the same time, many livestock interests, hunters, and hunting outfitters opposed the return of wolves. The stage was set for a political battle, and while the USFWS and wolf advocates formulated and proposed wolf reintroduction plans, wolf opponents put pressure on local and state politicians, held public meetings to voice their opposition, and threatened lawsuits to resist any federal proposals to reintroduce wolves.

Meanwhile, dispersing wolves from Canada were discovering vacant territories in prime habitat across the US border, and by1986 at least one wolf pack had established itself near Glacier National Park. Regardless of human plans about reintroduction, Federal law was clear: naturally repopulating wolves were completely protected. Some wolf opponents acted outside the law, however. For example, most lone dispersing wolves discovered in nearby Idaho were turning up shot. Yet it was likely only a matter of time before wolves would naturally migrate to Yellowstone and other wild areas of the Northern Rockies where they would face the least conflict and resistance. Thus, by the late 1980s, within the confines of the law, there were two wolf management choices: (1) let wolves return on their own; (2) speed up the process though active reintroduction.

The ESA has a provision that allows actively reintroduced populations of endangered species to be classified as “non-essential, experimental,” thereby allowing much more flexible management options. For wolves, this includes the lethal control of those that prey on livestock. This option would be much more acceptable to livestock interests than the more stringent protections that would apply to naturally migrating wolfs. Wolf advocates were divided. Some believed that there was no guarantee that two lone wolves of the opposite sex would naturally show up and meet in large wilderness areas like Yellowstone any time soon, especially since many were being shot; they also recognized that more flexible management options might reduce resistance from wolf opponents and therefore lead to fewer court battles and a greater chance of survival for reintroduced wolves. Others wanted to let nature run its course, preferring the near complete protection that would be afforded to naturally migrating wolves, regardless of how long it would take to repopulate the region.

In the end, active reintroduction won out. Wolf advocates initiated public education campaigns, and surveys showed broad public support for the restoration of wolves, especially by National Park visitors. In 1987 the USFWS issued a revised wolf recovery plan for the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment [2] setting as a goal a population of at least 30 breeding pairs of wolves for three consecutive years. In the same year the wildlife conservation organization Defenders of Wildlife created a fund that would compensate ranchers for verified losses of livestock to wolves [3]. While evidence would have to be provided that an animal was killed by wolves (not often easy to do), and while most ranchers are more inclined to prevent losses on their own, this goodwill offer to share the economic responsibility associated with wolves perhaps lessened some resistance from livestock producers; it would also probably give wolf advocates a stronger position in the continued legal battles over the interpretation and implementation of the ESA as it applied to wolf policy in the West.

By 1994 the USFWS had finalized a plan to purchase wolves from trappers in Alberta, Canada and relocate them to Yellowstone National Park and to a large wilderness area in central Idaho that had been identified as prime wolf habitat (largely comprised of the Selway-Bitterroot National Forest). The Nez Pierce Indian tribe had offered to help manage the reintroduced wolves in the latter region after the Idaho state legislature passed a law preventing state wildlife agencies from cooperating. The first Canadian wolves were brought into Yellowstone in January 1995 where they were held for acclimation until late March, when 14 were released into the park with great public fanfare. During 1995 and 1996 a total of 66 wolves were released in Yellowstone and Idaho.

Like the wolves of the Midwest following ESA protections there, the wolves of the West did well, exceeding early expectations in the rate of their expansion, both in numbers and territory. At least in Yellowstone this initial rapid expansion was probably largely due to the over-abundance of prey such as elk. Not having experience at eluding wolves, the prey animals were not only numerous but were probably also easier targets than their more wary counterparts to the north.

As a result of the success of already reintroduced wolves, additional planned translocations were cancelled. By 1999 there were 115 wolves and at least ten breeding pairs in Yellowstone, 120 wolves and at least ten breeding pairs in Idaho, and about 75 wolves in Montana (where, as naturally established wolves, they had full ESA protection). By the end of 2002, the wolf population in the Northern Rocky Mountain DPS reached the biological recovery criteria of at least 30 breeding pairs of wolves for three consecutive years, and by the end of 2004 there were an estimated 835 wolves and 66 breeding pairs in the tri-state area (source).

In many areas of the Northern Rocky Mountain region wolves have continued to thrive, despite an overall mortality rate averaging 25 percent per year [4]. By the end of 2011 the population of wolves living in the Northern Rocky Mountain DPS was estimated to be at least 1774 (up 3% from 2010), with at least 287 packs (up 18%) and at least 109 breeding pairs (down 2%) [8]. Wolves have expanded into eastern Oregon and Washington, have shown up in northern Utah, and two wolves radio-collared in the Yellowstone region have been found dead in Colorado – one apparently hit by a car on I-70 west of Denver in 2004, and one poisoned by Compound 1080 (which is prohibited) in the western part of the state in 2009.

Yet this expansion has not been without challenges and setbacks for the wolves. The wolf population in Yellowstone, which peaked at 174 in 2003, has not climbed as high as was originally expected based on prey availability [5]. Outbreaks of distemper, parvovirus, and mange periodically hit the wolves, resulting in significant population declines in 1999, 2005, and 2008. The population in the park has recently declined further from 124 wolves in 2008 to an estimated 97 (with eight breeding pairs) at the end of 2010, likely due to a smaller elk population, inter-pack conflict, and mange [6]. According to a study analyzing wolf mortality data between 1982 and 2004, wolves were also not thriving in Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area of Montana, with not one wolf pack entirely contained within Glacier National Park [4].

Nevertheless, the current number of wolves throughout the northern Rocky Mountain region is a success for an endangered species and apex predator that had been virtually eliminated. As mentioned in Part 3, the return of the wolf has led to more historically typical biodiversity and ecological conditions in Yellowstone and elsewhere. While severe winters and drought have also been important factors, the elk population in Yellowstone has declined to half of what it was before wolves returned, to what is likely a more sustainable level. Bison may be benefiting as a result [14], as are beavers and all the animals their engineered wetlands support (e.g., waterfowl, muskrat, mink, moose, and fish). Cougars have retreated to their more typical highland haunts, and a greatly reduced coyote population has reverted to a more historically typical ecological role, preying mostly on smaller animals and carrion. Meanwhile the presence of wolves is contributing significantly to the economy of the region, as tens of thousands of tourists had spent an estimated $35 million through 2009 in coming to see and hear the wolves of Yellowstone.

At the same time, conflicts with human interests are on the rise and there is increasing opposition to wolves, including calls for the predator to be eliminated entirely from the landscape once again. In 2009 losses of livestock to wolves averaged about 1.7% of all losses throughout Wyoming, Montana and Idaho [7]. In 2011, 193 cattle or calves and 162 sheep or lambs were confirmed killed by wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain region, with $309,553 paid in compensation; 166 wolves were legally killed for depredation control [8]. (In 2010 the numbers were 199 cattle or calves, 249 sheep or lambs, and 2 dogs, with $453,741 paid in compensation and 260 wolves legally killed for depredation control). While these losses are a small percentage of the total, many livestock producers operate on slim margins and any additional losses can be very hard to take [10]. As well, it is difficult to measure the reduced productivity that occurs for cattle and sheep made nervous by the proximity of wolves. Livestock management practices are evolving in order to minimize the losses, including prompt removal of animals that have died from disease, birthing problems, or accidents; the use of guard dogs, electric fences, and fladry; and there are local programs coordinated by conservation organizations such as Defenders of Wildlife in which people monitor wolf packs and report their locations to ranchers (the Range Riders program, for example, is a for-pay job giving an opportunity for outdoor enthusiasts to experience life on the range).

Overall, deer and elk populations have fared well in the West as populations of wolves have expanded. Between 1984 and 2010, the elk population in Wyoming increased by about 70% (from 70,350 to 120,000) and in Montana by about 66% (from 90,600 to 150,000); in Idaho they declined by about 8% (from 110,000 to 101,000)[11]. As expected by many biologists, there are local yearly fluctuations in elk and deer populations caused primarily by weather, availability of suitable habitat, disease, and human access and harvest, but there are also some circumstances in which wolves or other predators reduce or limit wild ungulate populations [12]. The situation in Yellowstone has already been described. In Glacier National park, where wolves prey more on deer than elk, the elk population has been relatively stable. Elk numbers have declined recently in northern Idaho, and while a study showed that wolves may have been partially responsible in some areas, the regional decline is likely mostly due to other factors such as deteriorating habitat, human hunting, and a harsh winter in 2007-2008; predation by cougars and bears is also a factor [13]. Overall numbers of elk in the state are relatively stable, and while the elk harvest in Idaho has declined recently from an historically very high peak in the mid-1990s, it is averaging higher than was typical during the 1950s through 1970s when there were no wolves. Nevertheless, some (but not all) hunters and their political supporters blame wolves for any declines in elk populations or harvests, whether wolves are responsible or not, and some fear the predators are “overrunning” the West and won’t stop until all the elk are gone.

The legal status of wolves in the West has been volatile. On March 28, 2008, gray wolves in the northern Rocky Mountain region, including the entire states of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, as well as portions of Utah, Oregon, and Washington were removed from the federal Endangered Species List and wolf management handed over to the states. The goal of 30 breeding pairs for three consecutive years had been met, the wolf population was doing well in the region as a whole, and, as required, the states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming had developed management plans that were deemed acceptable by the USFWS. While all three state plans would allow hunting of wolves to prevent livestock depredation and limit their overall numbers, wolf advocates were concerned about Wyoming’s plan. It classified wolves in the northwestern part of the state – the greater Yellowstone ecosystem including Yellowstone and Grand Teton National parks – as trophy game animals subject to a licensed hunting season (excluding the areas where the state has no authority to manage wildlife: the two National Parks and the Wind River Indian Reservation), but all other wolves in the state were classified as predators that could be hunted at will without limit. Soon after the delisting announcement, 14 environmental and wolf advocacy groups filed suit challenging the delisting decision, arguing that Wyoming’s plan in particular could not ensure the survival of a viable wolf population. On July 18, 2008, a federal judge agreed and issued an injunction restoring the endangered status of wolves in the northern Rocky Mountain region.

In May 2009, the USFWS tried delisting wolves again, this time only in Idaho and Montana; wolves in Wyoming, remained under federal ESA protection as an experimental, non-essential endangered species until the state would develop a plan acceptable to the USFWS (and federal judges). The federal government would monitor the effectiveness of the individual state plans and would allow the total wolf population to be controlled down to 450 wolves for the entire region. Wolf advocates challenged this plan, and wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain were again returned to federal protection when it was revoked by a federal court in August, 2010. The public debate became impassioned, with advocates on both sides holding protests outside of courthouses.

Current Status of the wolves of the West

In March 2011 a new agreement was reached between the USFWS and a majority of the plaintiffs which would have reinstated the delisting in Idaho and Montana while federal protections continued in and plans were developed for Wyoming, Washington, Oregon, and Utah. This agreement was denied by a federal judge in April, 2011, who found that delisting in the current conditions and with a few plaintiffs still in opposition was still not compatible with the provisions of the ESA. Almost simultaneously, and for the first time, the United States Congress became directly involved in the management of an endangered species, overriding the procedures specified by the ESA. The Congress attached a rider to the 2011 federal Budget Agreement that removed wolves from federal protection in Idaho, Montana, and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Utah; the rider also disallows further lawsuits to be filed regarding wolf management in these areas and reinstates a Wyoming U.S. district judge’s decision in 2010 that the USFWS wrongfully rejected Wyoming’s management plan. On May 5, 2011, the USFWS issued a "final rule" delisting gray wolves in the Northern Rockies region (excepting Wyoming) and handing management over to the states.

Following is a summary of the most recent status of wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain region state-by-state.Montana (updated March 2012):

At the end of 2011 there were an estimated minimum 653 wolves living in the state (up 15% from 2010), in 130 packs with 39 breeding pairs.

In May 2011, in a “final rule” issued by the USFWS subsequent to the passage of a rider to a federal Budget Agreement, wolves were removed from federal endangered species protection and placed under state management. State management plan goal (approved 2004): maintain at least 15 breeding pairs and 150 wolves; if less than 10 breeding pairs, revert to federal protection. Regulated harvests allowed to limit population. A hunting quota of 75 was established for 2009 and 72 were legally killed; the proposed quota for 2010 was 186, but the hunting season was precluded by federal re-listing. The quota for the 2011 season for the entire state was 220 wolves, with separate numbers set in 14 districts; the goal was to reduce the wolf population to 424 wolves by year end. The quota was not met by year’s end so the season was extended through February 15, 2102 (except for two units were the quota was met, comprising nearly half the state): a total of 166 wolves were taken during the season. [ Montana 2011 Wolf Hunting Guide.] In addition, 64 wolves were killed in 2011 for depredation control: 57 by federal Wildlife Service agents and 7 by private citizens (141 were killed in 2010 for depredation control).

Since the hunting quota was not met during the 2011-2012 season, state wolf management officials are proposing to allow trapping and electronic calls for future seasons. There is also a proposal to allow hunters to kill wolves believed to be responsible for depredating livestock outside the hunting season; livestock owners are currently allowed to kill wolves seen in the act of killing livestock. Meanwhile, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has agreed to hear a suit by wolf advocates that would stop wolf hunting in Montana and Idaho.

In 2011, 74 cattle, 11 sheep, 2 dogs, and 1 horse were confirmed killed by wolves, and $85,855 was paid in compensation (additional unconfirmed losses "most certainly occurred"). This compares with 87 calves or cattle, 64 lambs or sheep, 2 dogs, 3 llamas, 2 domestic goats, 1 horse, and 4 miniature horses, and $96,077 paid in compensation in 2010.

Statistics and quote for 2011 obtained from Montana Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2011 Annual Report.

Wyoming (updated March 2012):

At the end of 2011 there were an estimated minimum of 328 wolves (down 4% from 2010

and up 2% from 2009) in at least 48 packs with at least 27 breeding pairs. 98 of these

wolves were in Yellowstone (in 10 packs with 8 breeding pairs).

Wyoming Gray Wolf Recovery Status Report, January 2012

As of December 2011, wolves are federally listed as experimental, non-essential population; thus no hunting allowed but wolves depredating livestock subject to lethal control. In August 2011 the state reached an agreement with the U.S. Department of Interior that would remove wolves in Wyoming from the federal endangered species list; the proposed rule is currently under scientific peer review and a period of public comment. The agreement specifies that the state will maintain a minimum population of 100 wolves and 10 breeding pairs outside Yellowstone National Park and the Wind River Reservation, and a minimum of 150 wolves and 15 breeding pairs statewide (including YNP and WRR). The agreement establishes the Wolf Trophy Game Management Area (TGMA) in the northwestern part of the state within which wolves will receive some protections (a regulated hunting season); the area’s boundaries will expand towards the southwest from October 15 until the end of February to better protect dispersers between Wyoming and Idaho during peak dispersal season. In addition to regulated hunting, wolves inside the TGMA will be subject to lethal control by Wildlife Service agents or livestock producers who find wolves in the act of killing livestock; wolves deemed to be negatively impacting elk populations may also be subject to lethal control; lethal control inside the TGMA may include aerial hunting. Wolves in Grand Teton National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and the National Elk Refuge will be managed by the federal government (hunting of wolves not currently allowed). Wolves outside the TGMA and the national parks and elk refuge will be killable any time without restrictions. WYOMING GRAY WOLF MANAGEMENT PLAN

In 2011, 35 cattle, 30 sheep, 1 dog, and 1 horse (which had to be euthanized due to a broken leg) were confirmed killed by wolves; 36 wolves were legally killed for depredation control. The numbers in 2010 were 26 cattle, 33 sheep, and 1 horse; and 40 wolves killed for depredation control ($73,490 paid in compensation).

Idaho (updated March 2012):At the end of 2011 there were an estimated minimum of 746 wolves (down 4% from 2010 and down 13% from 2009) in 101 packs (up 16% from 2010) with 40 breeding pairs (down 13% from 2010).

In May 2011, in a "final rule" issued by the USFWS subsequent to the passage of a rider to a federal Budget Agreement, wolves were removed from federal endangered species protection and placed under state management as a "big game" animal. The state’s wolf management plan of 2008 establishes a population goal of between 500 and 700 wolves. A hunting season was set for the fall 2011 with a harvest limit of 165 wolves in five management zones and no limit in nine other zones (a maximum limit of two wolves per hunter). The season will run from August 30 to March 31 in eleven zones and until June 30 in two zones (to be stopped if the quota is reached in a particular zone). Electronic calls may be used by hunters to attract wolves, but bait may not (although wolves may be "taken incidentally" to bear baiting); the use of dogs to pursue wolves is not allowed. A trapping season is in effect from November 15 until March 31, 2012 in northern and northeastern regions with no harvest limit although no single trapper can take more than three wolves; snares and leg-hold traps may be used. Meanwhile, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has agreed to hear a suit by wolf advocates that would stop wolf hunting in Montana and Idaho. Through March 2, 2012, 240 wolves had been legally killed by hunters and 101 had been legally trapped. [Idaho Wolf Harvest, 2011-2012].

During 2011, 71 cattle or calves, 121 sheep or lambs, 3 horses, 6 dogs, and 2 domestic bison were confirmed depredated by wolves; in addition, 19 cattle/calves, 26 sheep/lambs, 1 horse and 1 dog were considered “probably” killed by wolves. (The numbers of confirmed depredations for 2010 were 75 cattle, 148 sheep, 2 horses, and 1 domestic bison). Also during 2011, 63 wolves were killed legally for depredation control, 11 were killed or suspected to have been killed illegally, 7 were killed by humans incidentally, and 15 died of unknown or natural causes. During the 2009-2010 season, 186 wolves were legally killed by hunters; in 2010, 80 wolves were legally killed for depredation control.

2011 IDAHO WOLF MONITORING PROGRESS REPORT

Oregon (updated March 2012):As of the end of 2011 there were an estimated minimum of 29 wolves in eastern Oregon, in four packs in the northeast with at least one breeding pair, and at least six other known wolves (at least 4 known to be alone). In late 2011 a lone dispersing wolf was confirmed as the first wolf ranging west of the Cascade Mountains in 65 years (known as “OR-7” this wolf has travelled at least 1062 miles and has wandered in and out of northern California).

Wolves are listed as endangered throughout the state under state law; in May 2011, in a "final rule" issued by the USFWS subsequent to the passage of a rider to a federal Budget Agreement, wolves were removed from federal endangered species protection in the eastern part of the state but remain federally listed west of highways 395, 78, and 95. The Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management plan says the wolves will be "considered for statewide delisting once the population reaches four breeding pairs for three consecutive years in eastern Oregon," but adds that wolves in western Oregon will be managed as though they are listed "until the western Oregon wolf population reaches four breeding pairs." The plan specifies that state and federal agents may kill wolves believed to be involved in chronic depredation of livestock, although non-lethal methods will be emphasized; livestock producers may harass wolves to distract them from livestock, but they must have a permit, issued if they witness depredations, before taking any action that may harm wolves. Once the management goal of seven breeding pairs is reached, a controlled hunt could be allowed "to decrease chronic depredation or reduce pressure on wild ungulate populations." Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan

In 2011 there were 20 confirmed livestock deaths caused by wolves (all calves or cattle); two wolves believed to be involved in chronic depredations were killed in May; two others were targeted for lethal control in September but the action was stayed by the Oregon Court of Appeals as a result of a lawsuit by three environmental groups. In response, a bill has been introduced in the state legislature to specifically allow wolves to be killed for depredation control; it has passed the House and is being considered by the Senate. In 2010, eight cattle or calves were depredated and no wolves were killed for depredation control.

During 2011 the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife sent nearly five thousand text messages notifying landowners of the proximity of wolves, and the Department maintains a weekly on-line map of wolf locations. The Department or livestock producers also employed non-lethal depredation control measures such as fladry, hazing, range riders, radio-activated guards (on radio-collared wolves), radio receivers (to receive signals from radio-collared wolves), bone pile removal and modified husbandry practices. Also in 2011 the state legislature established a fund to compensate for confirmed losses to wolves (but only if they have taken reasonable steps to minimize losses) and allocated $100,000 to assist private citizens with non-lethal protection and control measures.

Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan 2011 Annual Report

Washington (updated March 2012):As of December 2011 there are an estimated minimum of 27 adult and yearling wolves and three breeding pairs in the state; five packs are documented (3 in northeastern Washington and 2 in the Cascade Mountains) and there are possibly a few unconfirmed solitary wolves. Wolves are listed as endangered throughout the state under state law. In May 2011, in a "final rule" issued by the USFWS subsequent to the passage of a rider to a federal Budget Agreement, wolves were removed from federal endangered species protection in the eastern third of the state but remain listed in the western two-thirds.

The state’s Gray Wolf Conservation and Management Plan was adopted in December, 2011.

The plan sets a recovery goal of 15 breeding pairs for at least three years, distributed

in various parts of the state, and provides for non-lethal and lethal control to minimize

livestock depredation (by state/federal agents for wolves that repeatedly depredate and

by permitted livestock owners for repeated or in-the-act depredations) and predation

of "at-risk" wild ungulate populations (the latter only after the wolf recovery

goal for the region is met); compensation will be provided to livestock owners for

confirmed losses to wolves. Federal protection, while and where it applies, will

supersede state law. A new management plan will be developed to take effect once the

recovery goal is met; public hunting will be considered at that time (some hunter groups

and Indian tribes are lobbying for hunting now).

The Gray Wolf Conservation and Management Plan for Washington

There were no confirmed livestock depredations in Washington in 2009 or 2010.

Colorado (updated March 2012):Sporadic evidence of wolves in northern part of state. There is a "draft" wolf management plan and a "scoping" report, basically consisting of recommendations stating that wolves will be allowed to migrate to areas where they "find habitat" subject to management methods, including lethal and non-lethal, to "minimize" livestock losses, and to provide compensation when livestock losses occur. It is believed that there are too many elk in Rocky Mountain National Park and some are calling for wolves to be restored to the park. The reintroduction of wolves was mentioned in a US Fish and Wildlife management report as a possible solution to elk overpopulation in the Baca National Wildlife Refuge, but it is considered unlikely that this option will be pursued.

Utah (updated March 2012):Through the end of 2011, wolves are known to have sporadically wandered into the state (the first sighting of a pack occurred in 2010), but no permanent pack or breeding pairs are believed be resident; three cattle/calves and four sheep were depredated by wolves in 2010, and one wolf was legally killed for depredation control. The 2005 Utah Wolf Management Plan sets a general goal of allowing wolves to disperse into the state subject to control for "unacceptable" livestock depredation or conflict with management goals for other wildlife populations, and specifies that compensation will be provided for livestock losses. Utah Wolf Management Plan

In May 2011, in a “final rule” issued by the USFWS subsequent to the passage of a rider to a federal Budget Agreement, wolves were removed from federal endangered species protection in the corner of north-central Utah along the Wyoming and Idaho borders (north of I-80 and east of I-84) and are under state management there; they would be under federal protection and management wherever they occur elsewhere. In March 2010 a Wolf Management bill went into effect that stipulates that the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources is to prevent the establishment of any wolves in the state until they are “completely delisted” throughout the state under the federal Endangered Species Act and therefore subject only to state management. If that happens then the current state management place stipulates that once at least two breeding pairs of wolves successfully raise at least two young for two consecutive years, wolves will be considered established in the state and the current management plan will be replaced. The state’s official policy is to not allow the establishment in the state of Mexican wolves. In 2011 a bill was recommended by a legislative committee that would allow wolf hunting.

California (updated March 2012):A lone radio-collared wolf wandered from Oregon into Lassen County, California on December 28, 2011, the first confirmed wild wolf in the state since the last was killed in 1924. The wolf continued to roam about the northeastern corner of the state through early March 2012, when it wandered back into Oregon. Wolves in California will be under federal ESA protection; three environmental groups have petitioned the California Fish and Game Commission to also include wolves under the state’s Endangered Species Act (currently they are not).

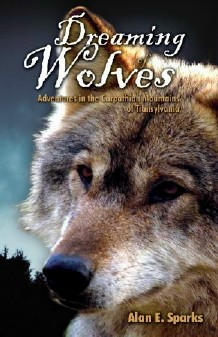

— Alan E. Sparks, author of Dreaming of Wolves: Adventures in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania

NEXT – Part 6: The Mexican WolfFOOTNOTES

- In the early days of the war against the wolf, it is likely that wolf numbers temporarily swelled significantly due to the slaughter of buffalo, which left millions of carcasses scattered over the landscapes of the west.

- See The Status of the Wolf Part 4 for an explanation of DPSs. The NRM DPS now includes Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and north central Utah.

- Total payments from DOW’s Wolf Compensation Trust between 1987 and October, 2009 totaled $1,368,043 in 893 payments (including compensation for losses to Mexican wolves in the Southwest). As of 2010, compensation for livestock losses to wolves will be funded by the federal government, so the Trust is transitioning to focus on working with ranchers to better coexist with wolves. Source

-

D.W. Smith, et. al. “Survival of Colonizing Wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains of the United States,

1982–2004”, Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(4):620–634; 2010.

The report includes a breakdown of wolf mortality as follows (this is prior to hunting which was allowed for some periods in Idaho and Montana): 30% legal control, 24% illegal kills by humans, 12% natural causes, 21% other causes such as strife or vehicle accidents, and 12% unknown causes. http://www2.allenpress.com/pdf/wild-74-04-04.pdf

Between 1999 and 2007, the overall mortality rate for wolves in the Greater Yellowstone Area averaged about 17%. 73% of this overall mortality was human caused. It is believed that an overall mortality rate exceeding 30 to 40% will depress wolf populations. -

The wolves in Yellowstone National Park are probably the most watched and intensively studied wolves

in the world, and fairly exact statistics are available about their diet:

“Project staff detected 268 kills (definite, probable, and possible combined) made by wolves in 2010, including 211 elk (79 %), 25 bison (9%), 7 deer (3 %), two moose (< 1%), two pronghorn (<1%), two grizzly bears (< 1%), four coyotes (1%), two ravens (< 1%), 4 wolves (1%), and ten unknown prey (4%). The composition of elk kills was 25 % calves, 43 % cows, 18 % bulls, and 15 % elk of unknown sex and/or age. Bison kills included four calves, six cows, seven bulls, and eight unknown sex adults.”

WYOMING WOLF RECOVERY 2010 ANNUAL REPORT - Between 2007 and 2010, wolves have declined less in the interior of the park (23%) than in the northern areas (60%). It is believed this is due to less canine disease in the interior (because of a lower density of canines: wolves, coyotes, and foxes) and the fact that in the interior a more significant population of bison is available as prey, offsetting the reduced elk population. WYOMING WOLF RECOVERY 2010 ANNUAL REPORT

-

Data from the National Agriculture Statistics Service.

Some breakdowns:

Montana:

Sheep and lamb losses 2009 (to wolves/total): 700/56,000 (1.25%)

Wyoming:

Sheep and lamb losses 2009 (to wolves/total): 600/45,800 (1.3%)

Cattle and calf losses 2009 (to wolves/total): 600/52,000 (1.15%)

Idaho:

Sheep and lamb losses 2009 (to wolves/total): 1200/28,000 (4.3%)

(This was a dramatic increase from 2008 when the loss to wolves was 2.7%)

Note that in all areas, losses of livestock to coyotes was much higher than to wolves, averaging over 20% of total losses. About twice as many sheep and lambs were killed by foxes than by wolves in Wyoming and Montana in 2009. In Idaho, while losses of sheep and lambs to wolves increased from 700 to 1200 from 2008 to 2009, losses to coyotes dropped from 7000 to 5400. - Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Program 2011 Interagency Annual Report

- Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 2010 Interagency Annual Report

- Could reduced losses to a reduced number of coyotes more than compensate for increased losses to wolves? A question requiring further research.

- Data from the Elk Population Reflects Success of RMEF’s First 25 Years, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and Elk Hunt Forecast for 2010, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. Habitat conservation efforts have probably contributed to this trend. The number of elk in Wyoming in 2010 was 33% above the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s goal for the state. Most of the decline in Idaho has occurred since 2007 (when there were about 125,000 elk) and numbers were still at or above objectives in 22 of 29 elk hunt zones in 2010.

-

See for example:

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game Elk Progress Report 2008

S. Benson, “Scientists: Wolves not decimating elk herds”, Idaho Mountain Express and Guide, January 12, 2007.

- Lundquist, L., "F&G: Wolves not causing most elk losses", Times-News MagicValley.com, July 31, 2010

- And to complete a natural circle, as might be expected in the complex and evolving world of predator-prey dynamics, in 2012 scientists confirmed for the first time that wolves in Yellowstone had learned to hunt bison.

[This article is current as of March, 2012. The status of wolves in the United States changes rapidly. Updates may occasionally be provided.]

© 2012, Alan E. Sparks. All rights reserved.

NEXT – Part 6: The Mexican Wolf