Complete Review

from Wolf Print Magazine

Issue 44 Autumn Winter 2011/2012 ; Pages 23-24

In 2001 and at 45 years of age, Alan Sparks had what some people might superficially call a mid-life crisis. But this was not a man in search of gratification from a red sports car or having his ear pierced. He was a thoughtful and compassionate person tired of being 'defined by his career.' Like so many of us, he needed to find some kind of connectedness, a purpose. But he also wanted to unwind, to unknot himself from routine.

After frustrating attempts to relax into the banalities of retail or to join the Peace Corps, Sparks looked inward. What were the defining passions of his life? His trilogy of wants would lead him to the Carpathian Mountains in Romania, a place that offered him the joy of mountains, cold weather and wolves.

This is a multi-layered book. Written in part as a diary, it mixes past and present tense so that the reader gets a sense of immediacy but also is allowed to look into the heart of the writer and understand a journey that is as much an emotional and intellectual one as it is physical.

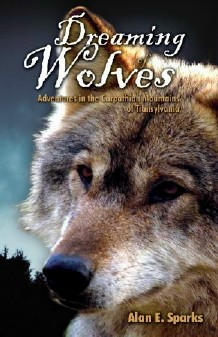

There is clearly a level of research, intellect and careful note-taking in Dreaming of Wolves, encompassing biology, history, politics, economics, animal conservation, philosophy and human relationships. There are also some beautifully glossy photographs which complement the book well and give the reader a vivid sense of the area.

Yes, it really is that rich.

Sparks initially wrote to Christoph and Barbara Promberger, the facilitators of the now-defunct Carpathian Large Carnivore Project (CLCP), offering his services as a volunteer. He wrote with sincerity, promising that he was fit and useful. He was accepted but immediately expected to leap in and muck in without much of a fuss. Rabies shots? Don't bother. Visa? If you need one, we will get one. Truly in at the deep end. Much later in his journey, he realised that the very fact he was 'working for nothing' made [some] poor struggling Romanians suspicious and resentful. It is a complex country, as he discovers continually.

There is the visceral and often brutal reality of living in large open spaces with large carnivores such as bears and wolves. There is folklore, long ingrained, which can work against any conservationist trying to dispel myths and fears. The country has over half a million Roma (gypsies) who fiercely defend their right to roam and graze their animals, in a wildlife-rich wilderness where life is relatively simple, but hard. The wolf in particular can be seen not only as an enemy but as a supernatural presence; amber eyes in the darkness.

Sparks' adventures include border wars with fiery locals, language problems and

the ever-present spectre of human greed that pushes the desperate farmer into

cruel and cunning behaviour. One incident in particular is not for the squeamish,

or the sensitive. It is a difficult job, trying to communicate the larger picture,

the longterm aim: large carnivores will attract tourists and ultimately generate

money and work for local people. Sparks, although he avoids sentimentality and

romanticised clichés, can still write with elegiac passion about his incredible

surroundings and the people who populate it:

'…women in flowery dark dresses and wide-brimmed hats… little girls trailing

at the end in purple and white dresses….'

Romania is a place of peculiar contrast, at once thick with religious devotion but

also ruled by much dark superstition. The shadow of Dracula and all things Gothic,

cannot be shaken from the region. Sparks sees a cart carrying a dead man and cannot

help but give himself a moment of pure whimsical reflection about the man being

a vampire. He sees:

'…a man's large nose sticking up from a thick bed of flowers.'

Death is not hidden away and whispered about in Romania. It is everywhere. A large part of volunteer work is to track wolf kills in daylight, to read and record what they find after the lupines have completed their nocturnal activities and their bellies are full enough to let them sleep.

Decapitated boars, foxes and deer are common finds. 'Find the head' becomes something of an ominous mantra, but that is not the extent of the gruesome duties expected of him. There is wolf scat to analyse. There is also meat to hack – mainly dead horses – then to store until it grows so putrid it has to be burned. Scavengers of all descriptions have to be driven away.

At CLCP, there are two socialised wolves to feed who, like the wolves at the Trust, are ambassadors for canis lupus. But Crai and Poiana are not the only animals around the wolf cabin. Coexistence with animals is compulsory and that includes leeches, mice, snakes and flies.

I was actually most impressed and moved by Sparks' deep and respectful bond with animals; first with his own beloved dogs and then later with the shepherd dogs that are around him, in particular a dog called Guardian, who disappears. His fate is only discovered near the end. Sparks always keeps emotions in check and never resorts to anthromorphism in his writing – so that sense of quiet love is all the more powerful.

When the scientists are observing wolf behaviour and to some extent other animals, there are interesting observations that come to the fore, such as wolves seemingly using a slide repeatedly. For fun? It certainly appears that way. Or one wolf removing an irritating parasite from the other, in a way that is generally more common in apes and monkeys. Logic and rational science does not always explain away such behaviours. It is a reminder that information we analyse from observing wolf behaviour in particular is still evolving, challenging us and our previously held beliefs. Sparks always gives us a calm and measured account, quoting from experts like David Mech. There is a lot of pertinent information in the book, such as how and why wolves vocalise.

Sparks could have very easily remained in Romania. He was certainly sad to leave. But he makes it very clear 'I didn't come here as a tourist.'

His final exit from the country made me cry. Mainly because he appeared so changed and moved by his experiences. It was clearly something that would stay with him forever.

This is indeed the book written by an incredible observer of character and landscape, a sensitive listener and ultimately a passionate conservationist. 25% of the author's royalties goes toward various wildlife conservation projects. To quote more from the book, although tempting, would seem like giving away treasures. Buy it, read it carefully. It's a book I will not be letting anyone borrow. It has a heart and a very powerful one.

Alan E Sparks makes an incredible statement of future intent that we should all,

as conservationists, as human beings, take as our own:

'I seek to be aware. I seek to notice.'

Exquisitely said.

– Julia Bohanna © 2011 Wolf Print Magazine

Back